Sitting in the Dark with Henry Chalfant

A 40th anniversary screening of 'Style Wars' (1984) prompts a deeper look at graffiti's significance in my own life.

On Saturday, I sat in a darkened theater at Carnegie Museum of Art watching a 16mm print of Style Wars, the seminal documentary by Tony Silver and Henry Chalfant about the early days of New York’s hip-hop scene and its exploding culture of graffiti writers—future legends like Taki 183, Stay High 149, Dondi, Seen, Futura, Revolt, Zephyr, and so many more. I tried to recall when I had first seen the film. It debuted on PBS in 1984, when I was seven years old, so I know it wasn’t then. It must have been in 1991 or 1992, on VHS tape, around the same time I started writing graffiti.

As far as I was concerned, though, Style Wars was never Chalfant’s most influential work. For me, it was and always will be Spraycan Art, his 1986 book with James Prigoff that documented graffiti culture in America and around the world.1 I vividly remember buying the only copy on the shelves at the B. Dalton in Monroeville Mall. It would have been around 1992. When I got home I ran to my bedroom and pored over the pages. The book was not even a decade old at that point, but still it felt like stumbling upon some sacred text in a time capsule.

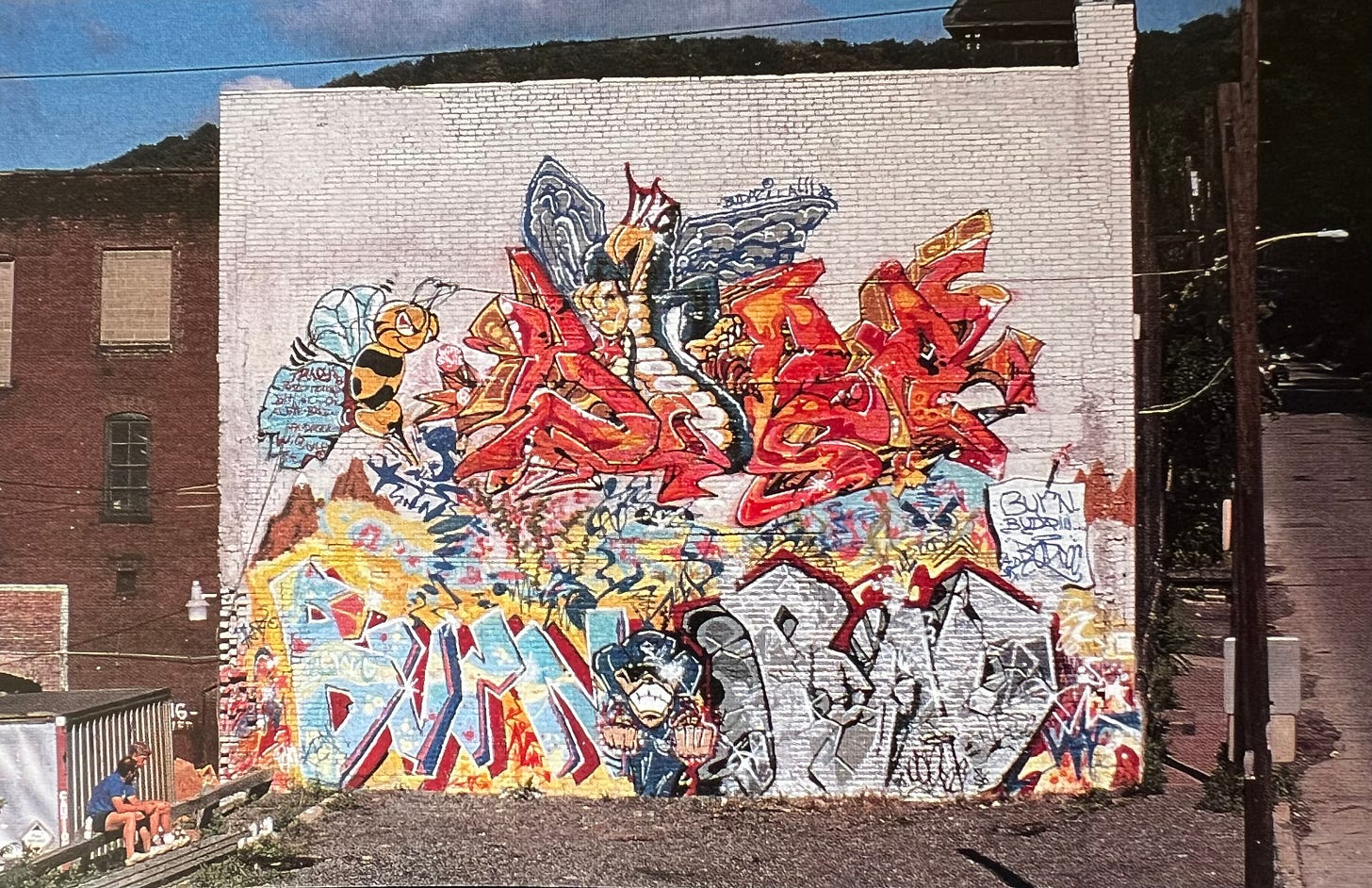

Not only did Spraycan Art offer a window into the graffiti culture in cities like New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Los Angeles, and more, it also included photographs taken in Pittsburgh—my hometown that I often wrote off as boring and behind the times—which blew my mind. Sure, Pittsburgh had to share a page2 with Cleveland, but still, we were represented. And representation matters—especially to a 14-year-old kid who had gone from sociable honor-roll student to becoming increasingly withdrawn from family and friends.3

What appealed to me about graffiti was its existence as a coded language. In the city, when I noticed Serg or Force marker tags on yellow traffic boxes, a little adrenaline rush kicked in. While I had yet to meet either writer, I knew them in the sense you know an author or musician: the work spoke for them. Handstyles fascinated me. Admittedly, I had little interest in painting pieces, probably because I’m not adept at drawing. But I did love bombing with markers, spraycans, shoe polish, paint pens, and any other tools that successfully marked surfaces. The mix of secrecy and destruction was addictive—I became obsessed.

In 2005, I wrote a cover story for the Pittsburgh City Paper called “Writers’ Bloc: Pittsburgh’s Graffiti Elite Confess their Obsession with Illegal Art.” The article looked at the past 25 years of graffiti in the city, from 1980 to 2005, and featured as-told-to narratives from nearly a dozen writers. Some were graffiti writers I used to go bombing with, others were either acquaintances or writers I never met. I also interviewed Henry as a sidebar for the piece, which is when I learned he was a Pittsburgh native.4 When we talked on the phone, I asked if he believes graffiti becomes an obsession.5

“It clearly takes over a person’s life,” he said. “It’s the combination of the hit of seeing your piece out there like that, and the knowledge that if you don’t keep doing it you won’t get anywhere. You can’t just do a piece and say, ‘Hey, I’m a writer,’ and be done with it, because it won’t be long and it’s all gone and you’re nobody.”

Re-reading this quote almost twenty years later, it reminds me that the Nobody vs. Somebody aspect of writing graffiti has always been a major draw. I know it was for me. While only a few of my friends and I usually painted together, knowing that a larger world of graffiti writers existed often gave us the sense of being part of something bigger.

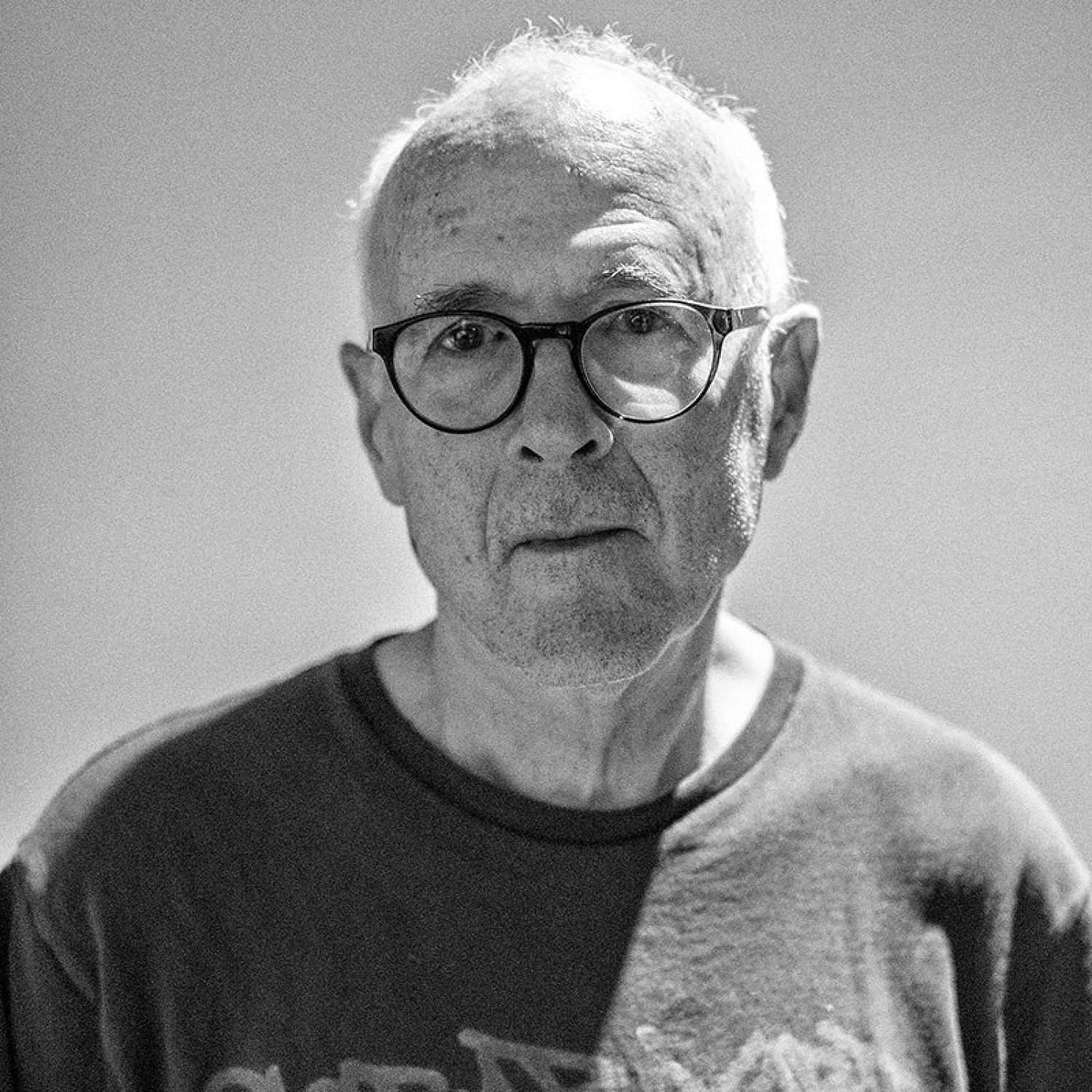

After the screening and panel discussion, I introduced myself to Henry, and mentioned our interview as an icebreaker. “Wow,” he said. ”That was a long time ago.” We talked briefly and he signed a 228 postal label for me (I forgot my copy of Spraycan Art). At the urging of my wife Michelle, I asked if we could have our photo taken together, and he humored me.

The importance of Henry’s photographs in my life is difficult to quantify. What I do know is that when I was slipping into the darkness of depression my freshman year of high school, graffiti was one of the very few beacons that I had.

On the day after the Style Wars screening, I showed my library of graffiti books to my son Nico, whose already attended graffiti workshops at the Carrie Furnace, and has an interest in the subject. After flipping through the pages of Subway Art and Spraycan Art, where I pointed out my favorite photos, he ran inside for his sketchbook and markers.

Endnotes

Chalfant’s Subway Art (1984), which he co-authored with photographer Martha Cooper, is, at least aesthetically, a much stronger photo book than Spraycan Art, which at times takes on an almost textbook tone. The design is also firmly rooted in the cheery, Day-Glo motifs of the 1980s.

Page 45 in Spraycan Art features photographs of two important pieces in Pittsburgh’s history of graffiti: Pop Life (1984) by Dasez and Smash and the massive two-story production by Buda, Badroc, and Burn (shown above).

By the time I was finishing middle school, I began to worry that something serious was wrong with me. In fact, I was right. Something was wrong. But my mental health issues didn’t fully reveal themselves for at least another year, when I started high school, which is a longer story for another time. But I do touch on this time period in my life in an essay called “White Rabbit” that I wrote during the first cohort of the Creative Nonfiction Foundation’s Writing Away the Stigma fellowship.

More precisely, he grew up in Sewickley, Pa.

My long-gestating thesis is that graffiti is an obsessive ritual that benefits greatly— both skill-wise and in the sense of relief it offers—from repetition.

It’s very interesting to know how you felt as a teenager. I didn’t know you were a tagged!