On the Phone with Harvey Pekar

In a fleeting moment of rash confidence, I decided to call Cleveland's curmudgeonly pioneer of autobiographical comics. Two decades later, our conversation still matters.

Twenty years ago, I called Harvey Pekar on the phone. I wanted to ask if he would write an essay for an anthology that I was editing called Fame & Misfortune. I was 28 and doggedly determined to do something. Establish myself. Become someone. The book, which centered on the perils of celebrity, was going to be published the following year via Poison Control, the small press that I ran out of my house. Pekar’s combative relationship with fame—and the fact that he had flirted with it for most of his adult life—seemed a perfect fit.

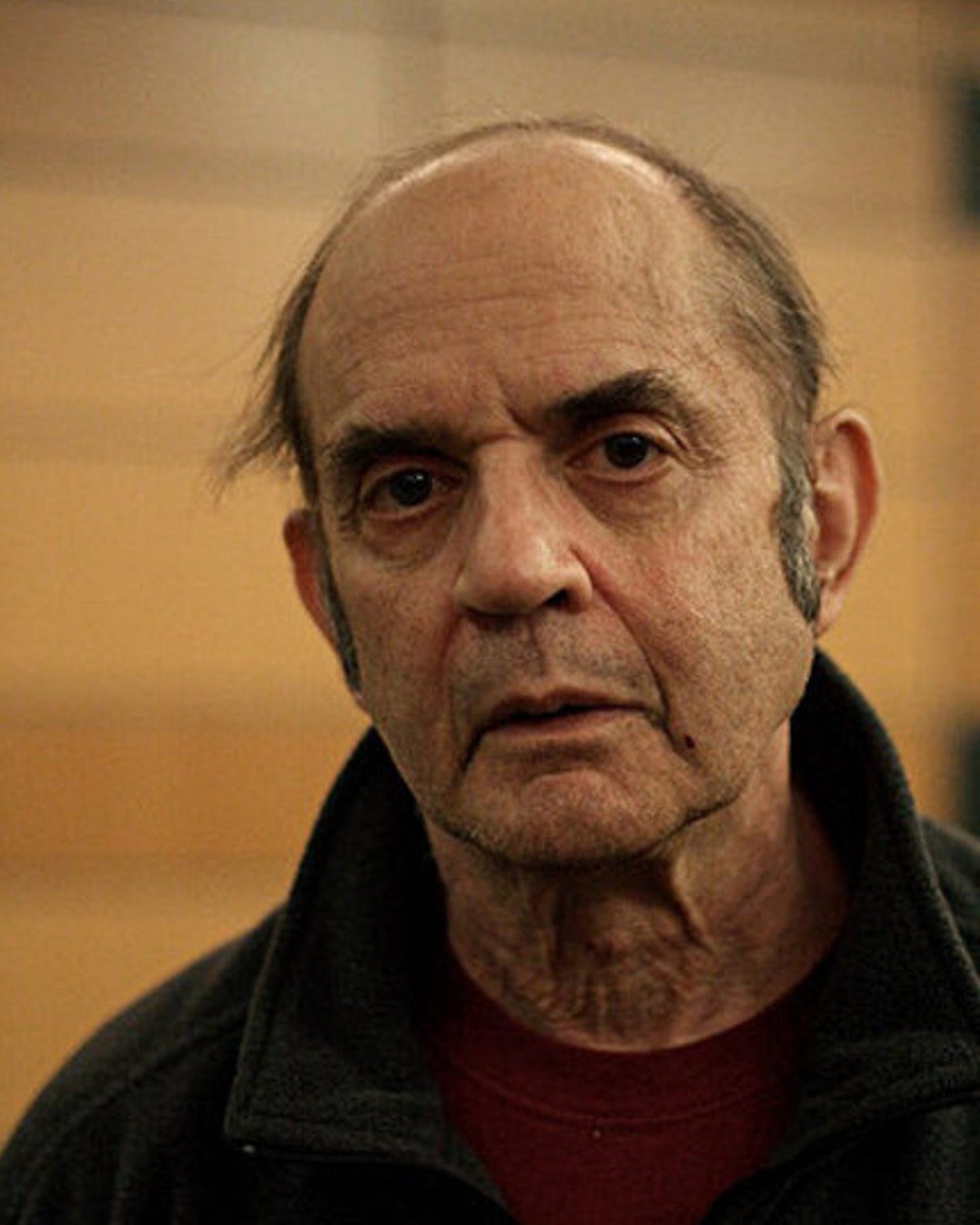

Pekar, for those not familiar, was a writer, jazz critic, and creator of the autobiographical underground comic book American Splendor, which debuted in 1976 and carried the tagline “From off the streets of Cleveland.”1 Pekar was a proud resident of Cleveland Heights, where he lived with his third wife, Joyce Brabner, a political writer and comics editor. When he died in 2010, at the age of 70, Pekar left behind a library of comics he created over his more than thirty-year career. Equally important to his personal mythos was what Pekar did during the day: he worked full time as a file clerk at the VA, a steady job that afforded him the freedom to moonlight as a comics creator.

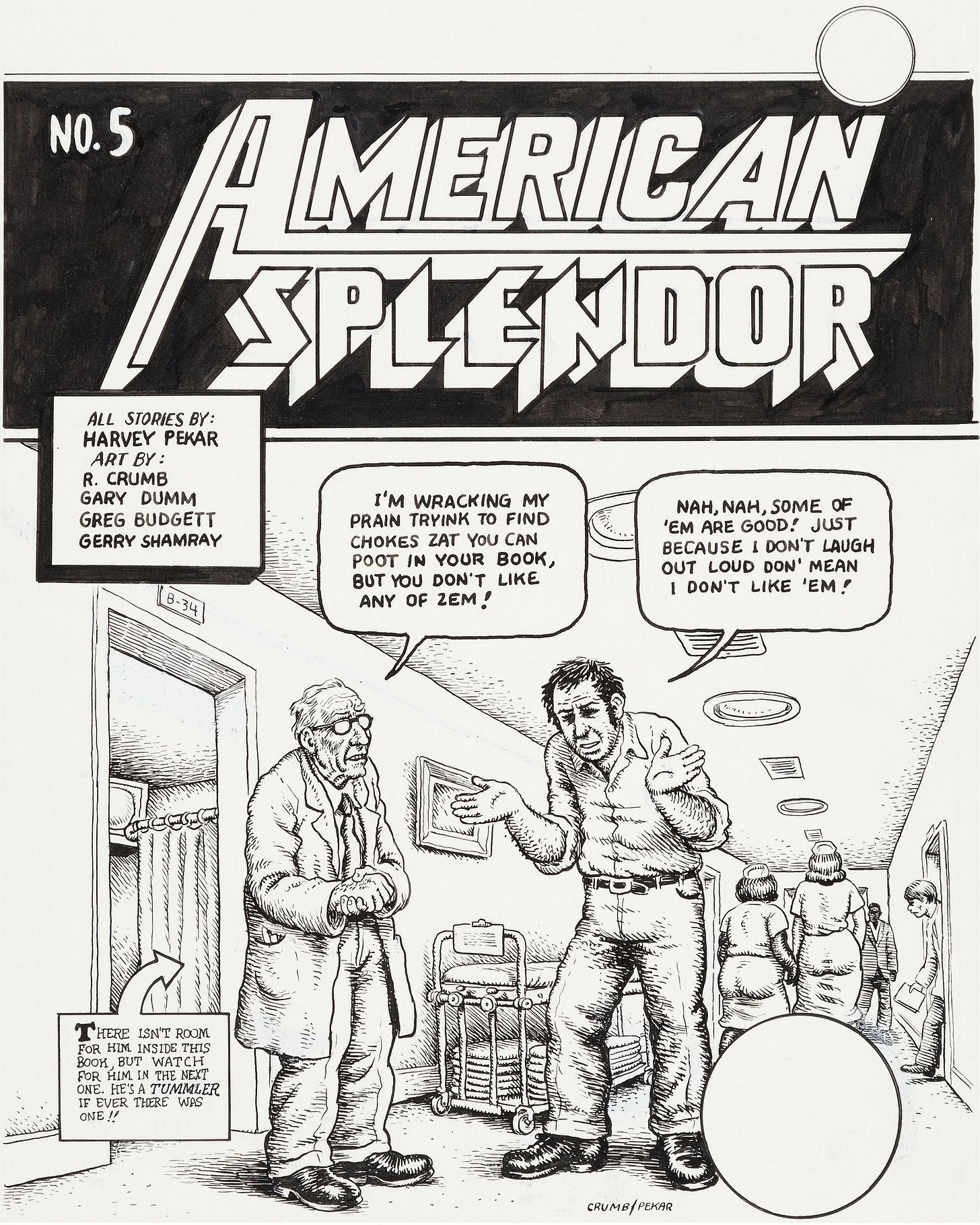

Comics is a visual medium, which makes Pekar’s place in comics history distinctive. He couldn’t draw. Instead, he relied on a revolving roster of cartoonists to help realize his stories. Some worked from stick figure drawings and dialogue he provided, others worked from short manuscripts or conversations with Pekar. His most frequent collaborators over the years were R. Crumb, Gary Dumm, Spain Rodriguez, Joe Zabel, Gerry Shamray, Frank Stack, Mark Zingarelli, and Joe Sacco. In the later decades of his career, Pekar partnered with a who’s who of independent cartoonists including Alison Bechdel, Gilbert Hernandez, Eddie Campbell, David Collier, Drew Friedman, Ho Che Anderson, and the late Ed Piskor.

This is probably what I admired most about Pekar. He didn’t let his inability to draw stop him from creating the pioneering comics that he envisioned in his head. As a writer who has loved comics and illustration my whole life, but who is hopelessly untalented when it comes to drawing, Pekar’s example has always inspired me. I still have time to write my own comic, I often think to myself. Harvey did it.

As Pekar described it, American Splendor was “autobiography written as it’s happening. The theme is about staying alive, getting a job, finding a mate, having a place to live, finding a creative outlet. Life is a war of attrition. You have to stay active on all fronts. It’s one thing after another. I’ve tried to control a chaotic universe. And it’s a losing battle. But I can’t let go. I’ve tried, but I can’t.”

I’d gotten Pekar’s number from a man who used to book him for speaking engagements. “Harvey’s real cool,” he told me. “Just give him a call.” So I did. The phone rang a few times, then Harvey picked up. His voice, scratchy and distinct, was recognizable from his days on Letterman, where his many appearances between 1986 and 1994 always left the show in total disarray.2 The only difference with this version of Pekar was the passage of time: he sounded like himself, but older.

Harvey listened patiently to my elevator pitch. I explained that this anthology, the second published by the small press I had founded a year earlier, was using essays, photography, and illustration to look at the cult of celebrity and the nation’s absorption in media culture, the subjective lens of the media, and celebrity worship. It was ambitious given my time and money constraints, not to mention my grand plans for who would be involved, how the book would be designed, and where it would be printed.

I was nervous, stumbled on my words, and probably sounded a bit manic. When I finished explaining the book, and what I was looking for in an essay, Harvey asked a few questions. How many words? What’s the deadline? He also told me the book sounded “real interesting.” Then he said: “What’s it pay?” That’s when my stomach dropped. I knew he would—and should—ask about payment. But that didn’t mean I was prepared to sound eloquent in my response. I think naive, 28-year-old me hoped he might not bring it up.

At the time, I had no money. Every submission I received was paid back in copies of books and zines, or by putting contributors in touch with editors and art directors I knew, people who could afford to pay them, however meager the money. But Harvey didn’t need that. He had an outlet for his work, a means of distributing his stories and ideas. That year alone, he had published The Quitter, an autobiographical graphic novel about his upbringing as the son of Jewish immigrants, and illustrated by veteran comic book artist Dean Haspiel. Best of American Splendor, an anthology of his work spanning the last twenty-five years, was also released.

“I’m paying for this book out of my own pocket,” I admitted to Harvey. “Which means my budget is almost non-existent.”

I was too embarrassed to tell him I would be printing the book after hours at the hospital where I worked at the time. And that I would most likely be sewing the binding by hand with my wife, and enlisting any willing friends to help as well. I knew that he, more than most, understood the challenges of independent publishing, but I felt so small time that I didn’t want to reveal the threadbare nature of my budding enterprise.

After admitting there was no budget, I waited for him to thank me for wasting his time. “I need to make some dough,” he said, before pausing. It seemed like he was mulling over whether he could handle doing one more piece of writing for free in his life. “Yeah, I need to at least make some dough, a few hundred bucks.” I told him I would see if I could get some cash together and, if so, I would call him back. I never got the cash.

When I think about this phone call, I cringe. I wonder if my request insulted him, even though he didn’t seem the least bit offended. To him, it was probably another phone call, one of many he fielded that day from his home in Cleveland Heights. But I wish I could have made it work.

In the intervening years, Pekar has become a hero of mine. At that time, however, I knew him more from Paul Giamatti’s portrayal in the film version of American Splendor (2003) and his Letterman appearances than his actual writing. Since then I’ve pored over his work, collected the original self-published issues of American Splendor, and even tracked down most of the title’s weird run on Vertigo, DC’s alt imprint. Occasionally I discover little-known stories by Pekar in obscure anthologies and one-shot comics I turn up in dollar bins at the local comic shop.

The Fame & Misfortune anthology remains unfinished, two decades later. And in that manuscript wasting away on an aging hard drive, there is no contribution from Harvey Pekar.

Endnotes

Pekar’s first critical writing was published in The Jazz Review in 1959. He also contributed hundreds of articles over the years to Downbeat, JazzTimes, The Village Voice, and The Austin Chronicle. “Harvey Sez,” a column Pekar wrote for comics anthology Weirdo from 1986–1990, looked at the contemporary comics scene.

Pekar’s Letterman appearance on July 31, 1987, where he wears a National Association of Broadcast Employees and Technicians (NABET) strike T-shirt, is one of my favorites. Not because his rabble rousing is particularly effective, but because his attack on General Electric, NBC’s parent company, unsettles Letterman to the point that his talk-show-host personality melts away and only frustration is left. It’s one of those rare moments of the real world sneaking up on an American television audience.

Holy cow was this such a good read. Talk about great writing. Wowza!