How Friendship Helped Author Hua Hsu Find Himself

In 'Stay True,' Hua Hsu's brilliant memoir about friendship and grief, "Recognizing oneself in the eyes of another" helped the author forge his own identity.

In 1994, Jacques Derrida published The Politics of Friendship, a book collecting a series of lectures the late philosopher had given on the topic a decade earlier. Friendship, he believed, represents a social bond that encourages us to envision a collective future untroubled—or at least less burdened—by the grave possibilities of the present. In other words, friendship, like any relationship with its own origin, history, and timeline, requires a certain suspension of disbelief that allows us to move through each day unbothered by the inevitability of loss and the fact of our own mortality.

At an atomic level, we are aware that all friendships end. We drift apart socially or intellectually. We no longer share the same interests, or laugh at the same jokes. Our moral compasses fail to align. What originally forged the friendship no longer sustains it. Or we become too busy with our own lives, whether raising children, working demanding jobs, caring for aging parents, or struggling to just get by. Tragedy steps in too, or illness, and friends are taken from our lives much sooner than we ever expected. But how do we prepare for these inevitabilities? Is it even possible?

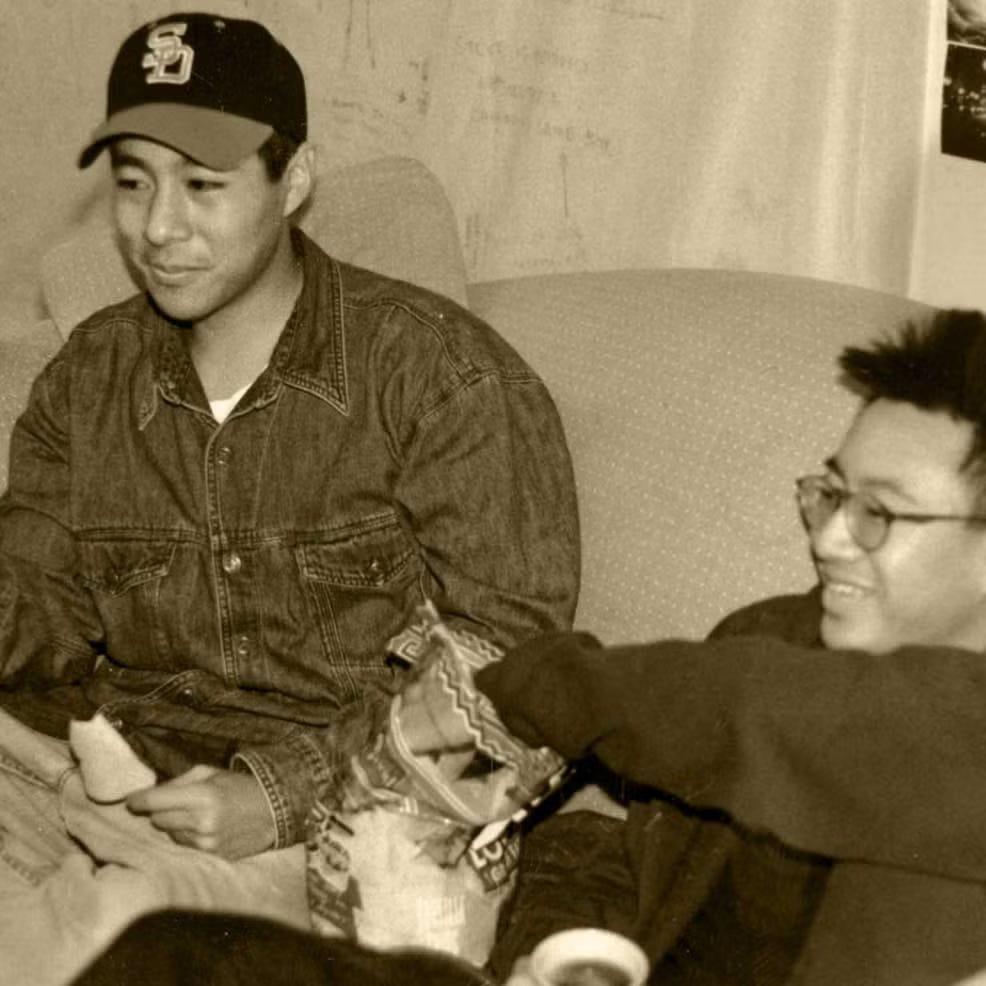

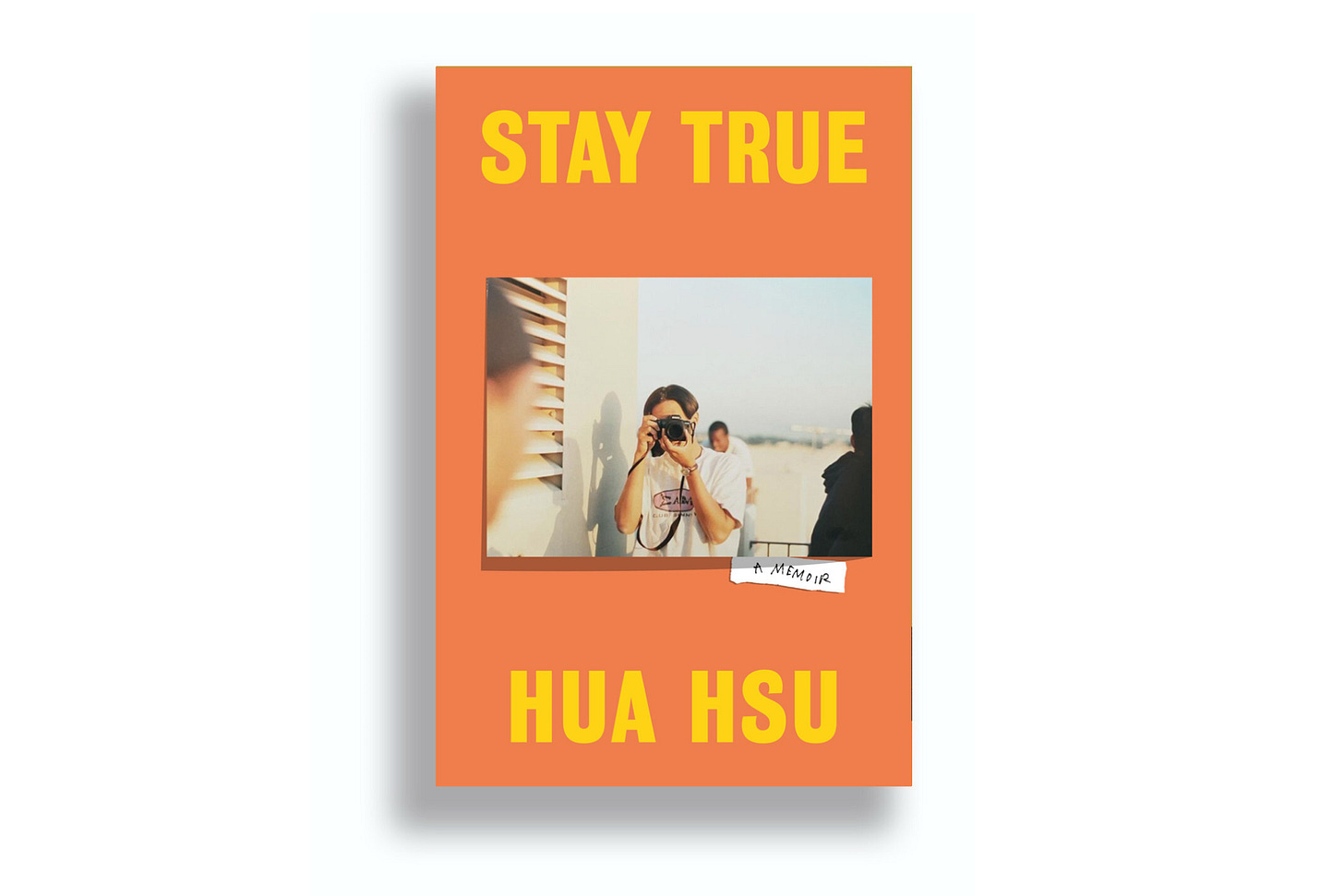

In Stay True, author Hua Hsu’s brilliant coming-of-age memoir, friendship is a central theme and so too is the grief that Hsu faces after his friend Ken is shockingly murdered during a carjacking. The latter detail, which is mentioned on the book’s dust jacket and defines much of its third act, still surprised me when it happened. That’s because Hsu and Ken are such complementary characters in each other’s lives that it became almost impossible to imagine one without the other. But that is the magic of Hsu’s writing in this memoir—it is honest and self effacing, funny and sad, but never overly saccharine or nostalgic.

Set predominantly in the Bay Area of the mid-1990s, with much of the narrative taking place on the campus at UC Berkley, Hsu strikes up an unlikely friendship with Ken, whose passion for music (Dave Matthews), fashion (Abercrombie & Fitch), and friends (he’s in a fraternity) couldn’t be farther from his own. Hsu frequents record shops, stays up late making zines, and carefully curates a closet of thrift-store fits. Yet the pair find commonality in their shared experience as Asian Americans and the unexpected ways their personalities and interests converge around music, culture, film, and philosophy.

“The intimacy of friendship lies in the sensation of recognizing oneself in the eyes of another,” Hsu writes in Stay True, paraphrasing Derrida. “We continue to know our friend, even after they are no longer present to look back at us. From that very first encounter, we are always preparing for the eventuality that we might outlive them, or they us. We are already imagining how we may someday remember them.”

In 2019, three years before Hsu published Stay True, he wrote about Derrida’s Politics of Friendship in a piece for the New Yorker, where he is on staff. What stands out to me in that piece is not so much Derrida’s take on friendship as it pertains to politics (because, if I’m being honest, reading philosophy often leaves my brain in knots), but in the realization that Hsu arrives at in the final paragraph of the essay, where, while not mentioned by name, Ken’s memory is ever-present:

My mind drifted toward more banal thoughts, such as whether modern politics is suspicious or unaccommodating of friendship, of the commitment to strangers that we assume as citizens. And then I thought about all the intimacies, shared over cigarettes and alcohol, on the edge of a tomb, which I had once tried to forget. Wounds of a different sort, the ecstasy of having once felt known.

In this passage from Hsu’s New Yorker essay—which, in slightly different form, finds its way into Stay True—you can see how Derrida’s writing flipped a switch in the author’s mind. “Recognizing oneself in the eyes of another” is the type of seemingly simple revelation you have as a writer that, in reality, is not at all so simple. As it relates to Hsu’s growth as a person, his ability to see beyond the artifice of Ken’s music and fashion choices is a watershed moment. Had he remained walled off, limited by his own tendency to pass judgement on people before actually knowing them, his friendship with Ken may never have existed. In many ways, Hsu’s emotional growth is the beating heart of the book, which makes the tragic third act that much more devastating.

After Ken’s murder, Hsu writes about the distinction between life with his friend and life without, and how he wanted his memories to act as an undisturbed archive:

I wanted to impose structure on all that had come before that July night [when Ken was killed], turning the past into something architectural, a palace of memories to wander at my own leisure. [Our friend] Sammi described us as “looters in a city on fire”; I nicked the phrase for later use. Your consciousness was like a city, and you scavenged and searched for treasured memories of better days. Or maybe memory is more of a fire than a city. It’s uncontrollable, fickle, and destructive.

At the core of Stay True is the idea that people are complicated, and that contradictions and incongruities can and do co-exist—whether in our friends or ourselves. In Hsu’s case, recognizing and embracing those idiosyncrasies was critical to the bond he and Ken forged, and eulogizing those memories in a book became the perfect tribute to a brilliant friend whose life was far too short.

Recommended Reading

“Stay True is as affecting as a great pop song.” —Jenn Pelly, Pitchfork

In the eyes of eighteen-year-old Hua Hsu, the problem with Ken—with his passion for Dave Matthews, Abercrombie & Fitch, and his fraternity—is that he is exactly like everyone else. Ken, whose Japanese American family has been in the United States for generations, is mainstream; for Hua, the son of Taiwanese immigrants, who makes ’zines and haunts Bay Area record shops, Ken represents all that he defines himself in opposition to. The only thing Hua and Ken have in common is that, however they engage with it, American culture doesn’t seem to have a place for either of them.

This piece contains affiliate links for Bookshop.org, a retailer that supports local bookstores. As an affiliate of Bookshop, Homesick earns a small commission when you click through and make a purchase there.