Harry Crews and the Death of Nostalgia

At its best, all good memoir writing should do this. Draw you in with experiences familiar and even universal, then upend that narrative with unexpected personal history.

To begin with Harry Crews make sense. After all, reading the Georgia native’s 1978 memoir, A Childhood: The Biography of a Place, is what prompted me to write Homesick. It helped me understand that personal history, while often viewed through the saccharine sweet lens of nostalgia, is most honestly written about when it includes the bitter parts we tend to hide away. Love tempered by heartache; joy informed by sorrow; peace attained through adversity; and the list goes on.

As Casey Cep wrote in a March 2022 article in the New Yorker, Crews’s memoir “animates nostalgia and then annihilates it.” I love this description. At its best, all good memoir writing should do this. Draw you in with experiences familiar and even universal, then upend that narrative with unexpected personal history.

In Crews’ writing, personal history and place are intertwined in such a profound way that, when written staggeringly well, as Crews does, a distinct and unshakeable voice emerges. This newsletter, in many ways, is about finding that voice. Not only for myself, but also in the work of others. Which is why Crews, with all his complexities and contradictions and raw abilities, is as good a starting point as any.

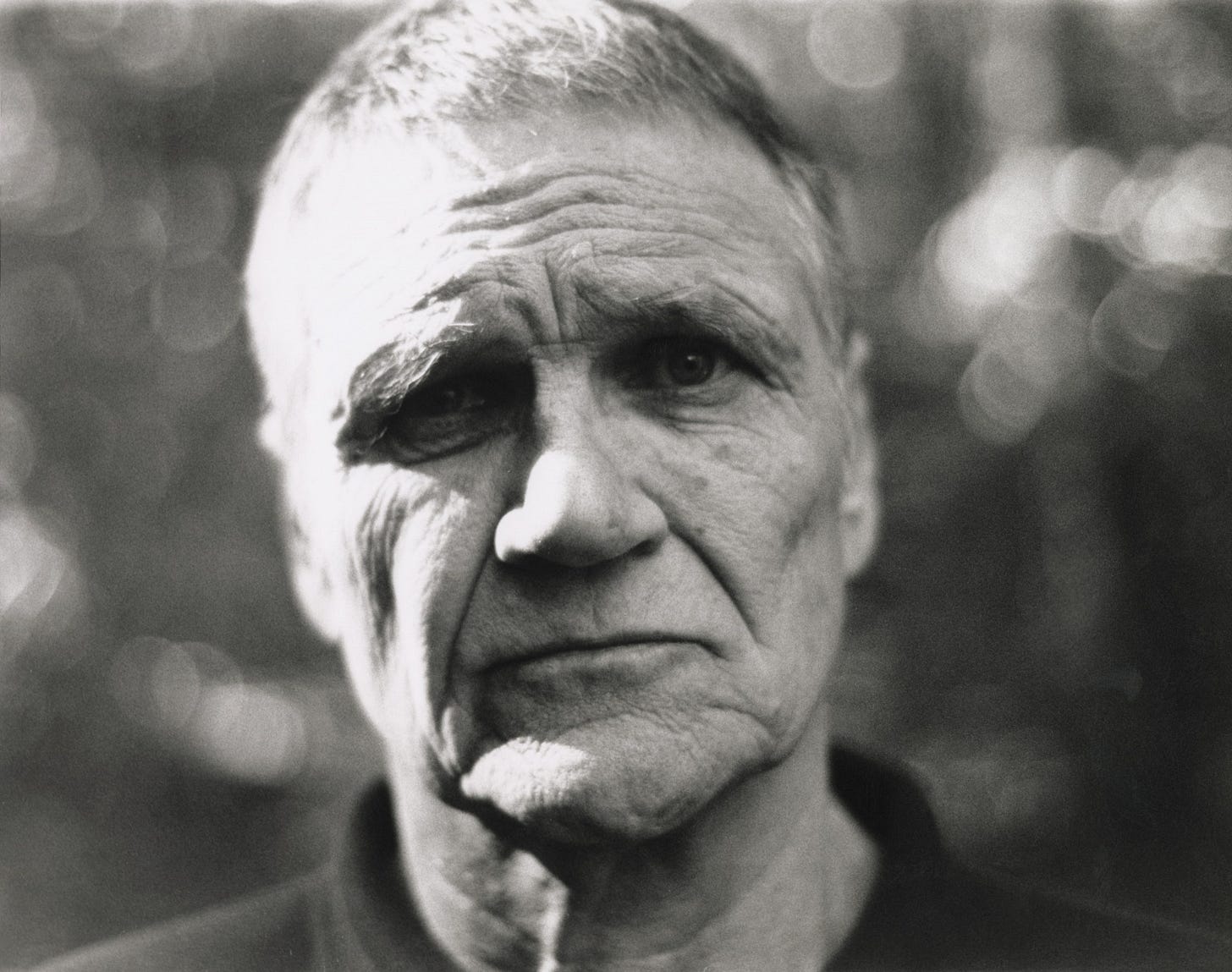

A harrowing but achingly beautiful account of growing up in the American South, specifically the first six years of his life, Crews, who died in 2012, had an intimate understanding of narrative voice and its significance. He knew how to translate the rich and lived-in worlds of his childhood in language both lyrical and profound. Nowhere is that more evident than in passages like this from the opening pages of A Childhood:

I had already learned—without knowing I’d learned it—that every single thing in the world was full of mystery and awesome power. And it was only by right ways of doing things—ritual ways—that kept any of us safe. Making stories about them was not so that we could understand them but so that we could live with them.

The phrase “live with them”—the stories, that is—infers more than one meaning. On one hand, Crews is talking about tolerance. To what degree can we tolerate the weight of our personal stories—both good and bad—and how much do we allow those stories to shape and define or even limit us. On the other hand, he is talking about how stories travel with us through our lives, and the ways in which we use them to explain ourselves or galvanize beliefs or mark time or reinforce our identities.

Not intended as a close reading of A Childhood, today’s newsletter is instead a point of departure for future issues of Homesick. (A close reading, however, would be great for a future edition.)

“To enter this book is to enter another world,” Tobias Wolff writes in the foreword to the Penguin Classics edition of A Childhood. “Though set in an American state—Georgia—in a time not too distant from our own—the first half of the twentieth century—any temptation to feel ourselves on familiar ground is continually revealed as illusion.”

Homesick is free. But it is also reader-supported. If you can afford to buy a subscription, I hope you will. Your contribution keeps the lights on.

All you can hope for, as a writer, is to build a world entirely your own. A place that you, and only you, are capable of rendering. Whether in truth or fiction, this act of creation is your fingerprint.

When I think of Pittsburgh, my own place of origin, arguably the largest, most metropolitan city in Northern Appalachia, but a city and region still plagued by income disparity, class division, racism, good-old-boy politics, and a growing divide between urban and rural populations, I consider how perceptions, identities, and beliefs have been shaped by voices past and present.

To claim authorship of a place is to assume a certain type of ownership over a larger narrative. And the concept of authorship is of course not limited to writers. In the dispatches, essays, and interviews published here in Homesick in the weeks and months ahead, the authorship of artists, filmmakers, historians, musicians, photographers, and more will be examined with the intention to cull insight or practical advice or a moment of clarity we never saw coming. At least, that’s my hope.