A Portrait of Joy in the Shadow of Collapse

Jack Teemer's kaleidoscopic color photography reveals a joyful portrait of postindustrial America at a tipping point.

A STRANGER WITH A CAMERA is a familiar figure in places where generations of working class families have lived in the shadows of industrial production. Places where you can see chemical processing plants from your backyard, or hear the mechanical thrum of an assembly line from your front porch, or smell sulfur as it burns off in clouds that carry downwind from the steel mill to the park where your children play. Whether that stranger is a documentary filmmaker, Hollywood director, television series showrunner, government film crew, or one of the many photographers or photojournalists who have pointed their camera at people in places where industry has poisoned the land, the pictures are made to communicate socioeconomic distress in simplified terms.

This is particularly true in places where visual representation has consistently been at odds with nuanced reality—from Rust Belt cities like Pittsburgh, Toledo, Detroit, and Rockford to small towns throughout Appalachia, which reaches from Southern New York down to Northern Mississippi, a sprawling geographic footprint spanning 423 counties across 13 states. Misrepresentation has dogged these places for generations, doing more harm than good. As author and critic Teju Cole has written, cameras are often their own type of weapon: “When we speak of ‘shooting’ with a camera, we are acknowledging the kinship of photography and violence.”

But there are exceptions.

In Rust Belt, photographer Jack Teemer’s brilliant photo book published posthumously by Nazraeli Press in 2019, two distinct yet uncommon qualities pervade the images: joy and empathy. To portray working class families as more than the collateral damage of globalism was a rarity in the 1980s, especially those living in places like Baltimore, Cincinnati, Columbus, Dayton, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh. But that’s what Teemer, a Baltimore native, was able to do.

In his own words, Teemer’s practice as a photographer was anchored by the concept of humane portraiture:

My photographs are beautiful because I need beauty, and organized because I need organization. It is also a way to entrust a sense of integrity for these people...I feel alive when touching these people’s lives, in the streets and in their personal spaces, particularly the people of a different culture or social class. I am reminded of what is truly important in life—love, empathy, and human relationships.

This approach, treating subjects with an abiding respect not only for them but for their spaces too, is telegraphed in nearly every image in Rust Belt.

Teemer, who died in 1992, was a lesser-known contemporary of photographers like Joel Meyerowitz, Stephen Shore, and William Eggleston. His photographs even appeared alongside theirs in the 1987 survey, American Independents: Eighteen Color Photographers, though his work remained under appreciated while he was alive.

“There’s sentimentalism in Teemer’s work that makes him stand out, and perhaps that’s one of the reasons he was overlooked,” Joseph Bellows, his gallerist, has said.

It could be argued, however, that the sentimentalism in Teemer’s photographs is what makes them so profoundly special. He was not in search of the beautifully banal pictures that Stephen Shore makes. Nor was he looking to conjure surrealist images from everyday life as Joel Meyerowitz has done for decades, or transform the ordinary into the poetic as William Eggleston has so often achieved. Teemer’s portraits carry emotional and contextual weight.

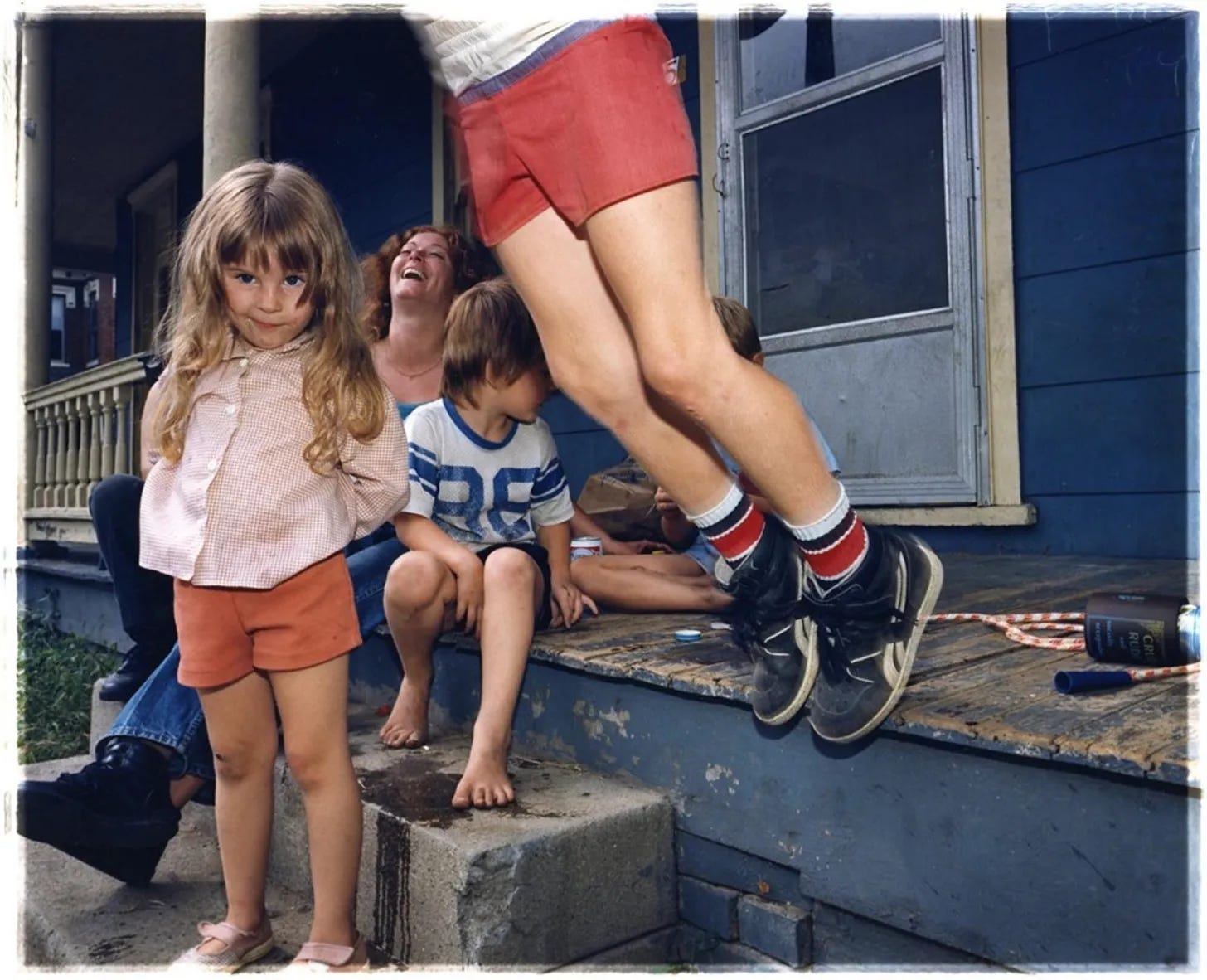

In none of the photographer’s images is this more apparent than in a photograph taken in Dayton, Ohio, in 1987, which is pictured above. A red-haired woman with her head thrown back in laughter sits on the steps of a front porch, accompanied by four children, all in different states of play. Your eye is drawn almost instantly to the young girl, who stands ready for her portrait. To the right, a young boy is seen mid-jump. Beside him on the painted floorboards of the porch sits a jump rope and discarded beer can in a cozy. In the center, a barefoot young boy is turned sideways, curious about what his friend or brother or cousin is holding in his hands. Look at this group as a whole, and the body language says everything you need to know about this moment—and others like it—that have most likely played out on this porch. Teemer just happened to be there to document it.

In American culture, the symbolism associated with the front porch can range from safety, shelter, and community to friendship and family. It is more than that too. The porch is a waystation between moments and moods and worlds—a threshold marking before and after or beginning and end. It is, as Michele Norris writes, “a transitional space between the cocoon of home and the cacophony of the outside world.” In the realm of postwar and contemporary art, the porch is what curators and artists would refer to as a “liminal space,” an inflection point between the present and the future, or a physical or metaphorical limbo that evokes feelings of ambiguity or unease.

In Teemer’s photograph, however, all subtext falls away. The porch, crystallized in this image as a place of joy and happiness, is nothing more than a well-worn, well-loved space where this family finds refuge on a hot summer day. And in this moment, that’s all that matters.

Love this.

I have been enjoying your posts very much.

Thank you for writing them